HMS Glamorgan

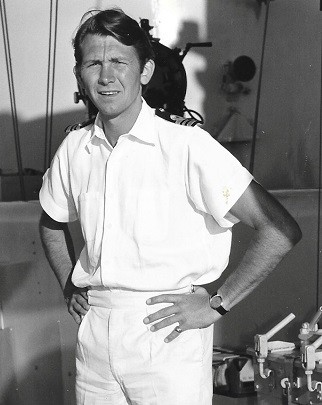

Reflections on a Falklands War Frontline Experience, Admiral(Retired) Sir Ian Forbes

HMS Glamorgan – Into War 1982

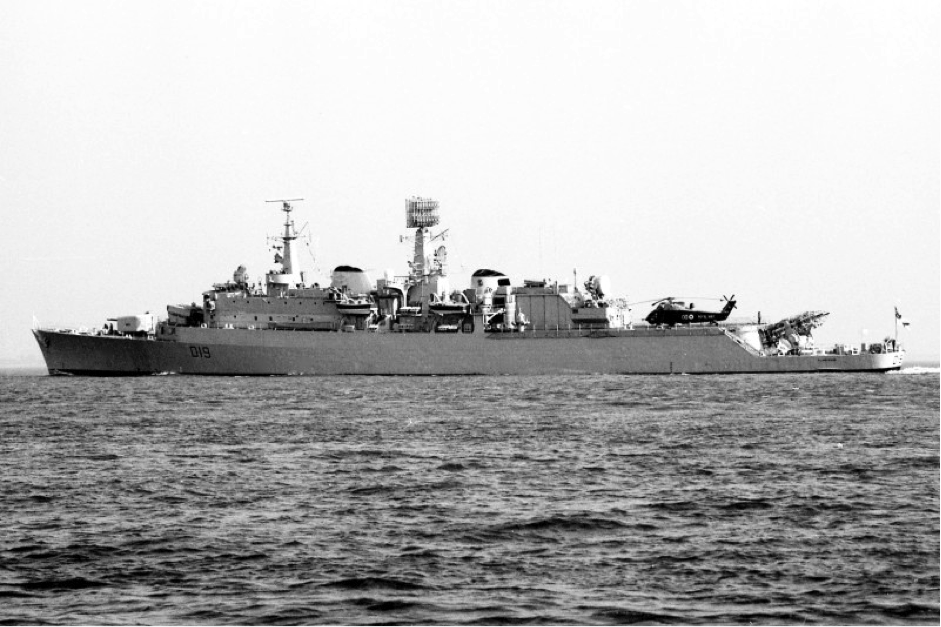

Over 35 years ago, in early 1982, when the World was locked into the Cold War, and Margaret Thatcher was in the second year of her premiership, I was serving in the Royal Navy onboard HMS Glamorgan, a Portsmouth based Guided Missile Destroyer, as the Operations Officer and one of 2 Advanced Warfare Officers with responsibilities for assisting the Command in fighting the ship. Glamorgan was the Fleet Flagship at the time, and had recently returned from the Middle East where Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward had been embarked, conducting exercises with the Americans and regional Navies. Exercises that were to prove invaluable to him when he came to be the seagoing Commander in the Falklands War.

In April 1982, we were operating off Gibraltar with a number of other ships, in a Fleet exercise designed to test weapon systems and crews in their readiness capabilities, when intelligence reports were received that indicated a group of Islands in the South Atlantic – the Falklands and South Georgia (that had been British Overseas Territories for nearly 150 years) had been invaded by the Argentines. Within days, a group of ships, including Glamorgan, were dispatched to head south to the Falklands as a contingency, their mission to prepare for war with the Argentines, and if necessary to force them to withdraw from the Islands. As we headed south, starting a voyage that would take us nigh on 4 weeks, we were kept aware of the multitude of global and national developments that were underway to bring about a peaceful solution to the crisis on the one hand, whilst making preparations that would enable us to fight and win a limited war on the other; because a limited war – and a vicious one – is eventually what it turned out to be. 255 British and 649 Argentinian military personnel were to die with many more wounded in the 10 weeks the War encompassed.

The memories of those of us embarked remain as vivid today as they were 35 years ago. The Royal Navy had not fought a war involving the use of military force of any consequence since Suez in 1957. So all of what we were experiencing was unexpected and unfamiliar. We had trained for war of course, but against a Soviet threat in the North Atlantic, not versus a South American state on the other side of the World. Indeed, the majority of people onboard had never heard of the Falkland Islands nor the fact that they were a British Dependency. Looking back, I doubt there were any onboard who had ever fired a shot in anger, even the Command. And that was common across the Fleet. There were a senior cadre of military personnel at the higher levels who had seen service in the Second World War, the Korean War, or at Suez, but that was the limit of the Services’ Real-World warfighting experience. A gap of over 25 years.

As we headed south, life onboard changed gear rapidly from its peacetime context to something utterly different. Material preparations ranged from topping up the magazines, to equipping everyone onboard with kit and survival gear. All unnecessary fittings were ditched overboard, including the Wardroom piano, and the ship’s interior became spartan in its atmosphere and feeling. Lighting was reduced, rations were cut down, water was restricted. In no time, we resembled a ship ready for war. Notwithstanding such physical activity, there were psychological and mental preparations to be put in place. A ship’s company of nearly 500 souls, ranging in age from 17 to 50, had to come to terms very rapidly with the prospect of going to war with all that it encompassed. In March, they had left home expecting to return to their families 6 weeks later. Now they were headed south to do battle against a foe they had never considered in a place they had never been. It was no good adopting an attitude that focused entirely on a peace process and returning home; the job was to be ready to fight and possibly to die. We all grew up very quickly.

It was a long trip south, nearly 8000 miles, with constant training throughout the day and into the night, that sought to counter what the Argentines might throw at us. The Argentine Armed Forces were thought to be less sophisticated than the British, but they had capability, and a fighting spirit, and the war if it came about would be fought in their backyard. Few underestimated the challenge. Air, surface and submarine threats were addressed, together with amphibious requirements, as it soon became apparent that retaking the Islands would mean landing a major Amphibious and Land Force on a hostile shore, without what was termed air superiority, not an operation that had been executed with any great success previously in history. And then fighting a land battle with the Argentine Forces who had invaded and established themselves, the term used is – well dug in – across terrain that was part bog, part peat, and frequently mountainous. Establishing a foothold on the Islands carried real risk, conducting a Land Campaign thereafter was going to be exceptionally tough going for all involved.

The Peace Process ebbed and flowed, led by the US Secretary of State, Al Haig, and right up until the eleventh hour, the prospect of a solution remained in play. But to most of us onboard, in week four of the passage, we had hardened our hearts to the prospect, and the focus onboard had become very businesslike. It would certainly be a baptism of fire for all, but there was a feeling that we were a taut ship, who had discharged herself well over the preceding 2-year period, and we felt ready. That’s not to say that there wasn’t nervousness at what might lie ahead, but our training was known to be first class, and we drew on that, and we felt the hand of history – the Royal Navy’s ethos and tradition – more strongly the closer we got to the Islands.

At War

Our arrival on 1 May needed all of this belief. Admiral Woodward sent Glamorgan to lead a group of 3 ships to get closer to the islands and test the Argentine’s reaction by conducting bombardment from our 4.5-inch guns into the Falkland’s airport area. Their reaction was robust, and we were bounced by a flight of Mirage Jets from the Argentine mainland, who came off the coast undetected, strafing us with cannon and dropping bombs. In Glamorgan, two bombs dropped either side of the stern, lifting us out of the water violently. At another time, under similar circumstances, we might have lost the stern or had our propulsion wrecked, but on this occasion, we survived, as did the other 2 ships, with only minor damage. Looking back, it would seem that the Argentines were as new to real warfighting as we were, and their approach and aim had fallen short. The feeling within the ship that evening was one of relief, but also of reassurance. We had been blooded, we had come through, and in a strange way, it settled the nerves and steadied the composure. It was very necessary, given what was to follow.

The weeks that followed were intense, draining, stimulating and at times boring. It soon became apparent to all that war was chaotic and unpredictable, involving lengthy periods of calm, where the imagination can run riot, and this all interspersed with sudden flashes of action that dispense death and destruction in minutes and seconds. Following 1 May, in the space of less than a week, the Argentine Cruiser Belgrano was sunk with significant loss of life, HMS Sheffield was hit by an Exocet and towed away to a watery end, Sea Harrier Aircraft were lost, and a number of other units suffered hits. People were wounded and died. Two colleagues with whom I had played squash in Gibraltar only weeks before perished onboard Sheffield; a friend from Naval College Dartmouth days died when his Sea Harrier blew up on launch for a night bombing mission over the Islands. So, things were becoming personal. It was clear early that we were facing a major battle, one in which more ships would be lost and with them people. A stock-take of the situation two weeks in suggested that the conflict was slightly more hopeful to us that it was to the opponent, and the increasing proximity of the passage south of a major follow on Force with the Amphibious Landing Group embarked raised our spirits no end. Momentum is an important factor in life and none more so than in the delivery of military force. The mood within the Task Group two weeks in was one of cautious optimism as we noted the full force of national power in all its aspects that was being deployed to bring the operation to a successful conclusion. Notable amongst this was the support provided by the United States in terms of strategic intelligence and cutting edge kit like the Sidewinder Air to Air Missile. We all knew by this stage that the campaign would be a long haul, but that it could not be too long. The advent of a southern winter loomed large in our thinking, introducing an urgency, indeed a necessity, to retake the Islands before the nights drew in and the Southern Ocean’s weather worsened.

Turning Point

If there was a turning point in the Campaign, it was between the dates of 21 and 28 May. They encompassed the landing at San Carlos, an extraordinary feat of arms, but at a cost. The losses of HMS Ardent, HMS Antelope, SS Atlantic Conveyor, and HMS Coventry, together with immobilising hits to a number of other ships. As expected, in assisting the landing and thereafter, the Surface Fleet was suffering damage that would be unsustainable over time. In particular, the loss of Atlantic Conveyor with its strategic reserve of helicopters was a major blow. But against this, the Argentine Forces were being inflicted with heavy losses. Their Navy had not reappeared since the sinking of the Belgrano, a factor that is frequently overlooked in subsequent debate concerning this event. Their Air Force operated with a boldness and skill that was unexpected and admirable, but the attrition in their numbers during this period was dramatic. Ashore, a largely conscript Argentinian Force, in Goose Green, Hamilton, and around the approaches to Port Stanley, the capital, were becoming ever more aware that their supply lines had been severed, and that a tried and tested force of Marine and Army professionals were on their way to engage them.

For us in Glamorgan, we had undertaken the Pebble Island raid on West Falkland with Special Forces embarked, and spent night after night on the gunline south of Stanley, pouring Naval Gunfire support inland to soften up the opposition and assist the Land effort. People had become used to the pace and the routine of operations, but a tiredness was setting in. Having been fully committed to the operation since the beginning, Glamorgan was sent to help in organising the multitude of merchant ships that were acting in support of the Task Group away from the threat further offshore. This allowed us a few days to refresh and reinvigorate; to digest letters from home that had only just arrived, our first contact since sailing from Portsmouth, and to reflect on a helter-skelter of impressions and thoughts that made up our preceding 10 weeks in which we had been engaged in the Campaign. In such times, there is a need to stand on the upper deck and breath clean rather than recirculated air, and then sleep in the knowledge that Action Stations will not be sounded or a hit sustained. The mind can wind down very quickly and then strengthen when these circumstances are in play.

Exocet Missile Hit

The major surprise to all in the Campaign, one that came from nowhere and caused the utmost anxiety, was the Exocet Missile, fitted to a number of Argentine ships and flown by a French made Jet – the Super Etendard. Glamorgan and other units in the Surface Fleet had their own Exocets fitted so we were well aware of its capabilities. We had practiced firing it in earnest, but given, as a French made missile, that it was unlikely to be fired at us, we had not practiced defending against it. So procedures and practices for doing this simply did not exist. Sterling work was conducted at ARE Funtington to put this in place, and it arrived with us as we transitted south as the Lead Group. Such work was done by a number of good people whom I know reside in Rowlands Castle, and still do. Members of the Task Group owe them much. They saved many lives for sure. The missile is a sea skimmer, with a clever seeker radar head, that has many built in features that allow for avoidance and lethality. Produced by the French, it became a ‘must have’ missile for many navies, for the punch it offered and the relative simplicity of its fit and operation. It is a sea skimmer as mentioned, optimised to penetrate the softer skin area of a ship. To do this, it travels at 700 mph to deliver a 364 lb warhead. Quite simply, it was – and probably still is – a deadly missile in all respects. Up to the point where Glamorgan was dispatched to assist the Merchant shipping, the ship had survived involvement in 3 Exocet attacks. Attacks that had been the cause of terminal damage to Sheffield and the Atlantic Conveyor. It would be no overstatement to say that an Exocet in flight raised the blood pressure of all and sundry across the Task Group.

On 11 June, Glamorgan was recalled from the Merchant shipping area, and ordered to resume overnight duty on the gunline to assist the Land Force in conducting its final assault on Stanley. This was duly done, although there was an added complication to the task than had been the case previously. Intelligence suggested that a shore based Exocet missile had been set up by the Argentines in the Stanley zone, and as a result a no go area was in place for ships to avoid when conducting the overnight operation. Glamorgan picked up activity in the evening much as before, undertaking Naval Gunfire in support of the Mount Kent operation ashore. When it came to leave at 0600, the ship delayed for a short period to assist the Land Forces’ (principally 45 Commando Royal Marines) final push.

At 0630, Glamorgan departed the gunline. Steaming at 20 knots to clear the area, indications of a potential firing of a missile from shore were detected on the bridge and from the operations room. This was validated soon after by radar and electronic means and the ship altered course hard to place the missile in the safest quadrant as advised by the ARE Funtington procedure. With less than 25 miles to travel the time of flight before impact was short and such early reaction was critical to the ship’s survival. But sadly, it was not enough to avoid the missile completely. It slammed into the port side of the ship aft of the funnel and just below upper deck level, burrowing along the deck to access the ship’s galley, before burning out and disintegrating. It left in its wake total mayhem. There was blast damage everywhere in its proximity, the hangar was on fire, the helicopter destroyed by fire, with live ammunition cooking off in the heat to hamper the efforts of the initial firefighters. Many of the Flight had been killed and wounded. Below in the galley, the blast had killed a number of the galley cooks and stewards and wounded others as the compartment collapsed and burned. Further across the ship, power was interrupted, floods began to take hold, largely due to a ruptured firemain, and the ship soon developed a list that hinted at a possible capsize and all that went with it. At one point in this situation, before our counter measures kicked in, it would be fair to say that our chances of survival looked very slim.

The countermeasures were legion. On the upper deck and within the galley, firefighting progressively brought the fire under control. The flooding was isolated and the list halted. Elsewhere, damage control measures were put in place, with switchboards and generators skillfully managed to generate the necessary power to float, to move, to fight. The ship was a first-generation missile destroyer and the missile – a Seaslug – the size of a London bus – was housed in a magazine that ran up the spine of the ship. With 36 missiles embarked, any detonation caused by fire could produce a reaction that would be catastrophic. We began firing them off as fast as was possible. And of course, we now needed to see to the dead, the dying and the wounded. The Wardroom became a hospital, its ante room a morgue. Our medical and Padre team were faced with a task that was beyond anything that they had previously encountered.

It sounds trite to say that the ship would not have survived without the teamwork that came into play on that day, but it’s true. As I mentioned earlier, we were a taut ship who had been together through some tough times. When the disaster happened, everyone, to a man, responded with an alacrity and an urgency that was critical in overcoming the life-threatening challenges we were facing. There were many acts of heroism that day. Firefighters moving into the flaming hangar to rescue and recover people. A young man swimming down a passage underwater with no breathing gear to identify and clear a jammed valve and reverse the flooding. Another young man in a Seacat launcher who got away a missile against the incoming Exocet that arguably diverted it just enough in its deadly flight to allow us to survive. When he emerged from his lonely upper deck position, to walk away, he found his director shield covered in shrapnel hits.

All of this and more allowed us to recover the ship, and we were soon underway to rejoin the Task Group, to be patched up and made ready should we need to go again.

As we made this journey, in the knowledge that we had survived, we had to come to terms with the aftermath. We had lost 13 of our Company, a fourteenth died later. And many others were wounded. So the immediate priority was to bury our dead and treat our wounded, either onboard or by flying them to other ships of the Task Group who were suitably equipped. None of us had contemplated or knew the details of a burial at sea, one that would involve saying farewell to so many of our shipmates. As we stood in the late afternoon light, I recall shafts of sunlight probing through the grey clouds. Some 400 of us stood on the Flight Deck at the rear of the ship, as a funeral ceremony was conducted, and our comrades were consigned to the deep. All I can recall is the utter sadness of the moment, and the fact that all of us who had survived had tears running down our faces.

Argentinian Surrender

Two days after our hit, on 14 June, the Argentines in Stanley surrendered. The mission to recover the Islands and once again have them under British governance had been successful. A grand endeavour in many ways. On the same day, Glamorgan was released by Admiral Woodward and told to return with HMS Plymouth, also damaged, to the UK. As we left, we passed close to HMS Hermes the Flagship and fired a salute from a worn out 4.5-inch gun. This was a hugely symbolic gesture for all of us onboard, because Glamorgan had been ‘down but not out’ and was leaving with her head held high. Our Falklands experience was over. We entered Portsmouth to an uplifting reception, albeit tinged with sadness at our losses, in early July. My family and I returned to Rowlands Castle that day, our haven then and our haven now.

HMS Glamorgan Association

Today, the HMS Glamorgan Association, established by our Captain, Mike Barrow after the conflict, is a vibrant one. Following Mike’s death a few years ago, I am privileged now to be its President. We have reunions every year at the National Arboretum in Staffordshire, where we have a Glamorgan bench around which we remember our fallen. Every 5 years, we have a reunion weekend with an evening event at the Naval Home Club on the Saturday, and a Church Service the following day in the Cathedral where we have a dedicated Glamorgan window in the Nave. As you stand and look at the window, at your feet are engraved the names of the 14 Glamorgans we lost in the conflict. At the 2017 reunion, we had over 300 people attending. The joy and pleasure at seeing each other at these events is palpable. A few years ago, the Association arranged for a large piece of Welsh granite to be taken to the Falklands by ship and then erected at Hookers Point with those same names engraved upon it. It is a fine memorial established as close to the point where it was thought the Exocet had been launched. It is looked after by local Falkland Islanders who recall with pride what Glamorgan and many others did for them.

But the Association is much more than an opportunity for Glamorgans to gather together and remember, important as that is. It is also a network of shipmates and their families to stay in touch, if necessary to assist each other in ways that were inconceivable all those years ago. Some Glamorgans suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and the Association has assisted them. Families of those lost keep in touch and draw strength from that. People are aware of others who have had difficulties in later life and alert the Association to help if they can. In all of this social media has facilitated a togetherness that is cohesive and helpful. And always, at the forefront of our collective thoughts, are a remembrance of those we lost all those years ago.

Aftermath

If I were to be asked, what were the outcomes of the Falklands Campaign, I would list four. One international, one domestic, one professional and one personal.

At the international level, it is difficult to recall now how fascinating the Falklands Campaign was for a watching World. It came from nowhere, it carried huge risk, and, given its context, with its imperial overtones, it could be termed a freak of history. If nothing else, as a NATO country, it demonstrated British will and military efficiency, something that would not have been lost on a watchful Soviet empire. It certainly changed Argentina, who soon swept away their Dictatorship in the aftermath of the War, embracing a South American model of democracy that has endured ever since.

Domestically, the Falklands Factor worked wonders for Margaret Thatcher. ‘Britain is great again’ she stated, and the Iron Lady image stayed with her as she took on the challenges of inflation, mass unemployment, the miners, and strikes. It undoubtedly stirred something deep in the British consciousness, and made many feel proud to be British again. Allied to this, the US/UK relationship was rejuvenated in the strength of the Thatcher/ President Reagan connection. Both were relatively new to office and formed a bond that was to be invaluable come the demise and fall of the Soviet Union a few years later.

Professionally, my experience was a searing one. Heading south to fight a war at no notice, from a distant location to a more distant one, calls for readiness of ships and men of a very high order. The Royal Navy advertises itself as a Force that is ready to fight and win, at any location from whence it comes. That the Service achieved this in the Falklands set a benchmark that stayed with me throughout my subsequent naval career. I was later to command in crisis at a number of levels. The maintenance of readiness was constantly in my mind.

And a personal reflection. I mentioned earlier that we felt the hand of history as we approached the Islands, drawing on the Navy’s lengthy tradition and warfighting ethos. This was readily apparent in the officers and men of HMS Glamorgan, and across the Task Force, who showed that they had lost nothing of the fighting skill and courage that the Royal Navy’s people have displayed down the centuries. It was my enduring privilege over 39 years of naval service to work with them.

So was it all worth it? Let me simply answer that with an anecdote. I have been to the Falkland Islands a number of times since the War. On one occasion I was talking with a young mother in Stanley (a place resembling a village anywhere in Britain) about her memories of that time. ‘You cannot imagine’ she said ‘the shock and fear of waking up in your home as a British person to find armed men at your front door demanding entry. And later, the same armed men booby trapping your baby’s empty pram as the British drew closer to Stanley’. That story captures my view entirely. The Falkland Islanders were British people, living peacefully as we all do, when their independence and way of life were brutally threatened. It was our responsibility and duty to come to their aid.

Editor: Sir Ian and Lady Sally Forbes have lived in Rowlands Castle since 1980

This article is by courtesy of Sir Ian Forbes who retains the copyright. 17-11-2017