Women’s Work in 1911

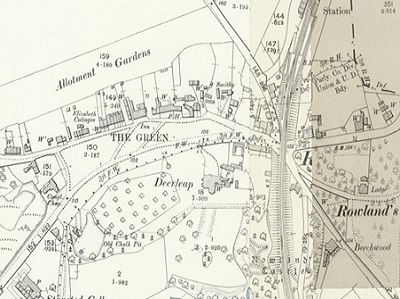

As the villagers of Rowlands Castle gathered on the Green to celebrate the coronation of George V on 22nd June 1911 it would have been hard to anticipate how village life was to change over the next ten years. The census, taken two months earlier, gives us a snapshot of a sleepy village which seems little changed since Victorian times, particularly for women. The 1911 census was the first national census in England in which the head of the household was expected to write directly onto the form to share their information.

The village of Rowlands Castle had grown over the previous ten years to a community of more than 100 households and the information requested was significantly more detailed than in previous censuses. Although there was equal space for men and women to complete their details in terms of employment and industry it is clear that there was still an expectation that a woman’s role should be played out solely in the domestic sphere. The most important information to be completed by married women related to their fertility and number of years married (1); this category was introduced for the first time in 1911 in light of a falling birth rate and increased emigration – the Government wanted to ensure a healthy workforce for the future.

The census as a protest

In towns and cities across the country- including in Portsmouth- the 1911 census was significant for many women as they used it as a way to protest. ”No vote, no census” was recorded in many of the returns (2). Emily Wilding Davison famously broke into the Houses of Parliament at Westminster and hid in a cupboard, so she could be recorded as residing there temporarily. At 4 Pelham Road in Southsea, Charlotte Marsh, aged 23, the organising secretary of the Women’s Suffrage League, “absolutely refused to fill out the paper” according to the enumerator’s notes. On the whole, however, the women of Rowlands Castle fulfilled their domestic duties and were largely noted with a blank space against their employment status. It is the employment of a few women that caught my interest as I transcribed the information of these households.

Shop girls

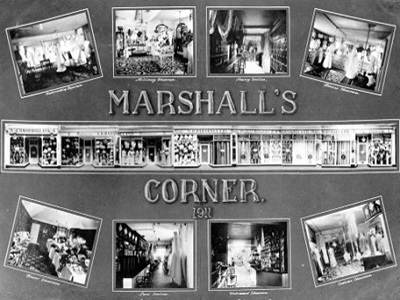

Eleanor Bayett, a 26 year old single woman, of Little Woodhouse, Idsworth, lived with her widowed father and worked as a Draper’s assistant, one of the few women who were employed outside the home. Ten years earlier she had been a domestic servant but now she was taking advantage of the employment opportunities available to women in the shops of the larger towns and cities – maybe she travelled by train to work in one of the larger stores such as Marshall’s Corner on Norfolk Street in Southsea.

Modern Technology

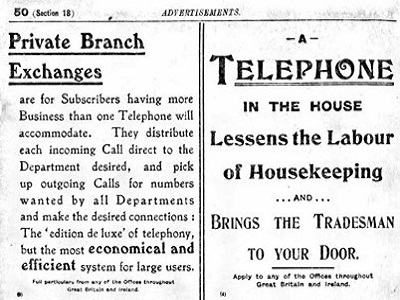

The Post Office and Telephone Corporation provided more local employment for women in Rowlands Castle. Kate Elizabeth Jeffreys of Elizabeth Terrace, a widow aged 44, was the caretaker of the Telephone Exchange of Portsmouth Corporation Telephones and Mary Smallbone, a married woman, mother of three, worked at home at Myrtle Cottage, as telephone operator for the National Telephone Corporation. The house is named “Telephone Call Office” for the village and uniquely, the male head of the house is employed elsewhere, leaving Mary to run the Call Office.

This was new technology, connecting the telephones of the larger houses in the village with other houses or businesses. Only a few of the larger houses had a telephone – they relied on the “Hello girls” working in the local exchange to make the connection for them. A few of the notable residents of Rowlands Castle are listed in the phone book for 1911(3). Major Dibben of Lynton Dene, Rowlands had his phone line – number 6Y, Admiral O’Callaghan at Deerleap was 9Y, the Brick and Tile works was 7Y. Mr Scutt the coal merchants was 7X; B and G Rook, the Grocers was Rowlands Castle 3 and Colonel Austen at the Red House was 3X. Although it seems incredible to think that women were at the forefront of this new technology, in fact it fitted well with the traditional idea that women’s nimble fingers, trained in needlework, were better suited to this employment than men’s fingers’

Traditional employment

Rowlands Castle in 1911 had its fair share of traditional female employment. Older, single women sought employment in domestic service or as dressmakers or laundresses, working from home, or in the home of their employers. The Clarke Jervoises at Idsworth House employed nine single women to keep their household running smoothly and many of the larger villas in Bowes Hill had at least one servant “living-in”.

Lydia Savage, a widow at just 34, was a Dressmaker working at home, while Maria Trimmer of Wellsworth, at the age of 66, took in laundry. Women of her generation had little education and she signed the census form with her mark, a cross. For a widow, with no other means of support, and often children to look after, employment of any kind was vital. At 1, Rose Cottage, Redhill Road, Eliza Hobbs aged 62, a widow, was an Apartment Housekeeper, with her 18 year old daughter assisting in the business. Their two visitors, of private means, came from Great Yarmouth to stay.

This is a photo of Mary Outen, aged 24, who lived-in as a domestic servant at the Red House, home of Colonel Austen.

In Finchdean a cluster of households record “Boarded Out children” all born in London and aged between 3 and 12. These families received a payment of about 5 shillings a week, and the children were generally orphaned or abandoned and placed into foster care by the Board of Guardians(4).

Educating women

There seemed to be little opportunity for women to take up higher education, although five of the six teachers listed in the Rowlands Castle census were female. Ellen Hilder and Mary Hill, unmarried women in their late 40s lived at Idsworth school to carry out their duties as Head teacher and Assistant head teacher. Gladys Canning, of “Rosemont”, Rowlands Castle, whose father was a dental surgeon, was perhaps indulged in her pursuit of education, being listed as a student at art school.

It is interesting to see this snapshot of village life in 1911 and intriguing to consider how things would change over the next ten years. What did those women do, who had no employment? What social circles did they move in? How did they contribute to the war effort after 1914, and did things change for them after the war? If you have a Rowlands Castle ancestor who is listed in the 1911 census, please get in touch and share your stories of their life.

References

1. 1921 Census. [accessed 4 April 2022]

2. National Archives on No vote, no census.

3. British Phone Books, 1880-1984, 1911-Southern, pp331-359, available via Ancestry.

4. The Boarding Out System [accessed 4 June 2022]

Editorial: This article was entered onto the website in June 2022 courtesy of Caroline Bird